Real-World Vision for AI

Vincent Sitzmann is revolutionizing how AI “sees” and interacts with objects

MIT is leading the way in AI and decision-making—the systems that allow interaction with the external world through perception, communication, and action. Vincent Sitzmann, the J. Burgess Jamieson Career Development Professor of electrical engineering and computer science and head of the Scene Representation Group, is revolutionizing how AI “sees” and interacts with the objects around it. His endowed professorship was funded by Burgess Jamieson ’52, whose prolific generosity takes the form of both outright gifts and a bequest.

Entering three dimensions. Sitzmann has always been fascinated with vision and perception. “Neither animals nor humans need very much time to learn how our three-dimensional world works, how they can move through it, and how to interact with objects in it,” says the assistant professor, who joined MIT’s faculty in 2022 after completing his postdoctoral research here. Before AI-enabled machine learning, computer scientists tried to manually encode the rules of perception and physics into computer programs with complicated formulas. “With the emergence of deep learning, a data-driven algorithm can learn for itself what to look for in video and what it tells it about how the world works,” he says.

One step on this path toward learning to understand our 3D world was “differentiable rendering”—algorithms that learn to create 3D reconstructions only from looking at 2D images. “My PhD research and work with fellow MIT researchers has pioneered techniques in computer graphics for generating photorealistic images of 3D scenes from a few image observations,” he says. “This class of techniques is what generates realistic bird’s-eye fly-throughs through Google Maps. You might soon see it in video games and movies, and you can already use it to record an interactive walk-through of your apartment.”

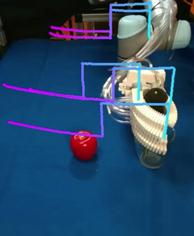

Democratizing robotic automation. Turning 2D images into 3D scenes just by “seeing” with a camera has huge implications for robots that interact with the world around them in real time, without painstaking programming. “Right now, code for controlling robots is written for precision-manufactured, big, expensive machines. We can’t use it for more affordable, mass-produced ones,” he says. “We are working to make robotic automation more affordable and democratize it, whether robots are helping humans in their households or enabling small businesses to automate their processes, even in remote parts of the world.”

For a recent paper, Sitzmann’s group collaborated with a local startup and Daniela Rus, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor of electrical engineering and computer science and director of the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, to create algorithms that can control cheap, 3D-printed robots that are more biologically inspired in their movements and functionality than their rigid metal predecessors.

“Our work shows what we can do without precision-engineered joints and precise sensors embedded in the robot itself. Instead, you point a camera at the robot, and the robot learns to move from vision alone,” he says. “It can look at itself in the same way you look at your own hand. What’s more, our algorithm can control robots that can be manufactured for much, much cheaper than existing ones.”

Research for the long run. “In my work as a professor, I want to work on ideas that are fundamental to the field,” Sitzmann says. “I’m thinking far out into the future.” Support like the Jamieson professorship, he says, is critical to maintaining the independence to do that curiosity-driven research. Jamieson created the professorship with an outright gift, then worked with the Office of Gift Planning to continue to support the fund with his bequest. “Since the funding is not coupled to any particular research direction, it enables me to take risks—to spend more time on research and less on fundraising. This is extraordinary.”

“In my work as a professor, I want to work on ideas that are fundamental to the field. I’m thinking far out into the future.”

He also notes that flexible funding for social events like group dinners for all members, from participants in the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program to postdoctoral researchers, plays a bigger role than one might think. “One reason, of course, is for overall mental health,” Sitzmann says, “but gathering in a social context is incredibly important for productivity—we’re all scientists, after all, and end up talking about our work in new ways.”

It’s that community that inspired him to become a professor in the first place. “The most brilliant students in the world apply to MIT,” he says. “Together, we can tackle the most difficult and challenging problems of our time.”

| Learn more about how to document your intentions for your estate plans, and contact the MIT Office of Gift Planning with any questions. |

Remembering Burgess Jamieson ’52

1930–2023

An electrical engineer, a veteran of the Korean War, and a pioneer of the venture capital industry, Burge Jamieson was committed to the development and nurturing of MIT undergraduates and faculty members through his generous philanthropy. A scholarship brought him to MIT—an educational award that he never forgot—and his planned and outright gifts to the Institute have been transformational for students and faculty members.

Burge met his wife, Elizabeth “Libby” Agate, then a Pine Manor College student, at an MIT dance that he helped organize. Married for 70 years, the Jamiesons raised their three children outside of Boston before relocating to the San Francisco and Silicon Valley area. They became ardent philanthropic supporters of the San Francisco Opera, the San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts, and the local San Mateo Historical Association. In September 2023, the newly renovated Innovators Gallery at the history museum was dedicated and named as a lasting legacy to honor his venture capital accomplishments.

At MIT, the Jamieson Endowment Fund continues to support undergraduate scholarships, the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program, two named professorships in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), and the Jamieson Prize for Excellence in Teaching Awards in EECS and the MIT Sloan School of Management.

When reflecting on the impact of MIT in his life, Burge summarized his commitment to the Institute in three words: people, teaching, and entrepreneurship. “It is a gratifying pleasure to be in a position to give back by helping to support men and women become promising MIT students, as well as to encourage and reward superior attention to teaching for deserving faculty.”